Zolatron: A homebrew computer of my own

There’s no better way to understand computers than to design and build one of your own. All you have to do is go back in time.

I’ve been writing about computers for a living for a few decades. Although not a professional programmer, I can knock out workable code in C, C++, Go, Python, JavaScript and other languages, and even had an app written in Objective C in the iOS App Store for a few years. And I’m a Certified Ethical Hacker, so networks hold no terror for me.

And yet… there is so much about how computers operate at a fundamental level that I grasped in only a vague, hand-wavy way. Lately, however, I wanted to know more. I wanted to see the bytes move and do their work.

Forward to the past

And so I chose to go back to the mid-to-late 1970s. That was when microprocessors first emerged. The Intel 8080 would spawn the first truly personal computers, most notably the Altair 8800 (which in turn gave rise to the birth of Microsoft — or Micro-Soft as it was then), the Imsai 8080 (a knock-off of the Altair but more professionally produced) and a raft of machines that shared the S-100 bus.

Microcomputers tapped into a reservoir of previously unserved desire — the urge to compute, to build and program machines that would obey your commands and even, on occasion, do something useful. Until then, computers had been the preserve of corporations, governments and major institutions. They were staggeringly expensive and required huge amounts of training. They were for grown-ups only.

Microcomputers — while still expensive by today’s standards — provided a route into this world for people with the dedication, passion and (in some cases) soldering skills. They released a flood of creativity.

This only grew with the release of further microprocessor chips, including the Zilog Z80, the Motorola 6800 and the latter’s bastard offspring — the object of my own desire — the MOS Technology 6502.

Best chip

To this day, nerds will argue endlessly about the relative importance, cleverness and, of course, performance of these 8-bit microprocessors. The Z80, for example, was the bedrock of the CP/M operating system. The 6502, on the ng the home computer revolution (at least, in the US).

For me, it’s a personal matter. The 6502 was at the heart of the BBC Micro, and that was the machine on which I really learned to program and which hooked me forever on computers. It was also responsible for my journalism career switching tracks, from photography to computing.

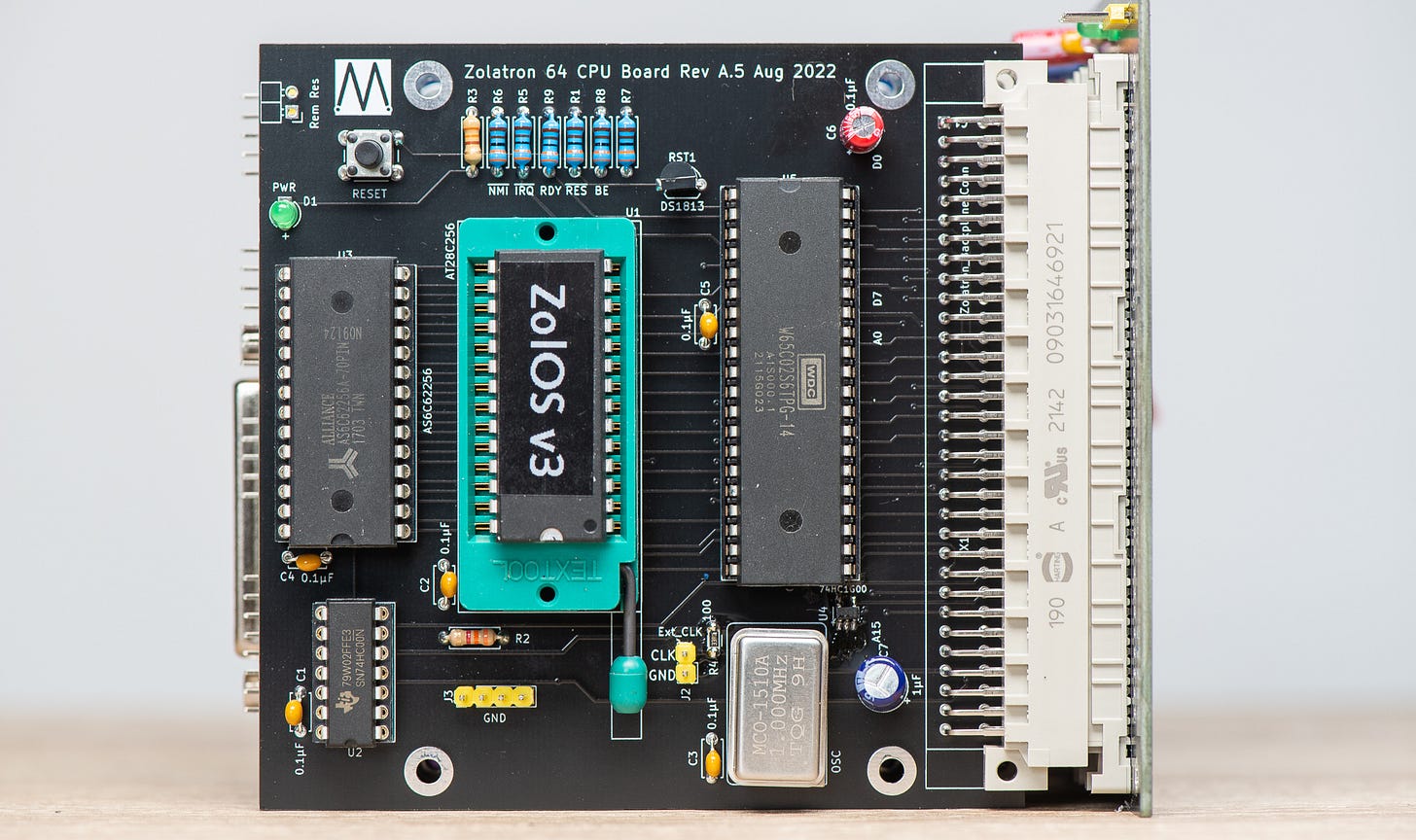

When I decided a few years ago that I would build my own computer, I knew it would have to have a 6502 at its heart. It would provide me with a chance to make good on a lost opportunity, because I knew I would be doing all the coding for this machine in assembly language.

That would address a nagging regret I’ve always carried about not getting into assembler back in the days when I was hacking on my original BBC Micro. I pretty much stuck to Basic, which was exceptionally good on the Beeb. As I’ve never been into games, I rarely wrote a program in which speed was an issue. So Basic gave me everything I needed. But I always felt I’d missed out on really understanding the computer at a deeper level.

I could correct this by coding in assembler on a modern x86 machine, but honestly, who wants to do that? Or I could write assembler for 8-bit AVR microcontroller chips — a place I have already dipped a toe (more on that in future articles). But there’s a simplicity about the old 8-bit micros that I like.

And this is an appropriate time to embark on this series of articles, as 2025 marks the 50th anniversary of the 6502’s introduction. The 6502 is still available to buy new — now from Western Design Center (WDC) which markets it primarily at the embedded controller market. How many pieces of technology have had that kind of longevity?

Where to start

So, with a project like this, where do you start?

For me, it was the name.

I landed on ‘Zolatron’. The ‘tron’ suffix was popular back in the 70s and 80s and so has the right period feel to it. And the ‘Zola’ bit comes from the name of our beloved spaniel who passed away shortly before I started the project.

He was a faithful companion and a great friend, obedient up to a point, with a tendency to suddenly wander off and do his own inscrutable thing. He could be infuriating but was always entertaining. I rightly predicted the project would share some of those qualities.

Next up was a logo—which I needed for many of the same reasons as the name.

What I came up with first employed a font similar to that used for the Commodore Pet. It also incorporated a photograph of Zola that, due to some hasty editing, accidentally made it look like he’s wearing a black turtle-neck. Maybe he’s channelling Steve jobs.

Later, I went for something vaguely inspired by DEC.

An actual computer

But enough of distraction activities. It was time to get to grips with hardware.

Computers are complex beasts. You can’t just plonk a 6502 into a breadboard and expect it to do something. It takes a number of components working together to make what you might call a minimum viable project.

That can create the kind of inertia that nips many projects in the bud. I decided I needed some help.

I turned first to the Apatco NCS 2056T. I don’t think it’s available any more, but it was a complete kit, including breadboard and components, that allowed you to build a very simple computer with a keyboard input and an LCD screen for output.

I never did get it fully working, but the Apatco kit contained some true gems — its manuals. They not only explained how to put the thing together but also delved deep into how the computer works, including critical concepts such as address decoding.

As I read the manual I could feel myself losing interest in finishing the kit — not because I wasn’t excited but because I was over-excited. I could already see how I wanted to diverge from the Apatco computer and exploit what I’d learned in designing my own system.

I’d already started doing that when Ben Eater began his justly popular series of YouTube videos about creating his own breadboard-based 6502 homebrew machine. I followed along for a while, recreating his machine. But again, I soon began veering off on my own tangent. One difference, for example, was in my choice of code assembler.

The journey

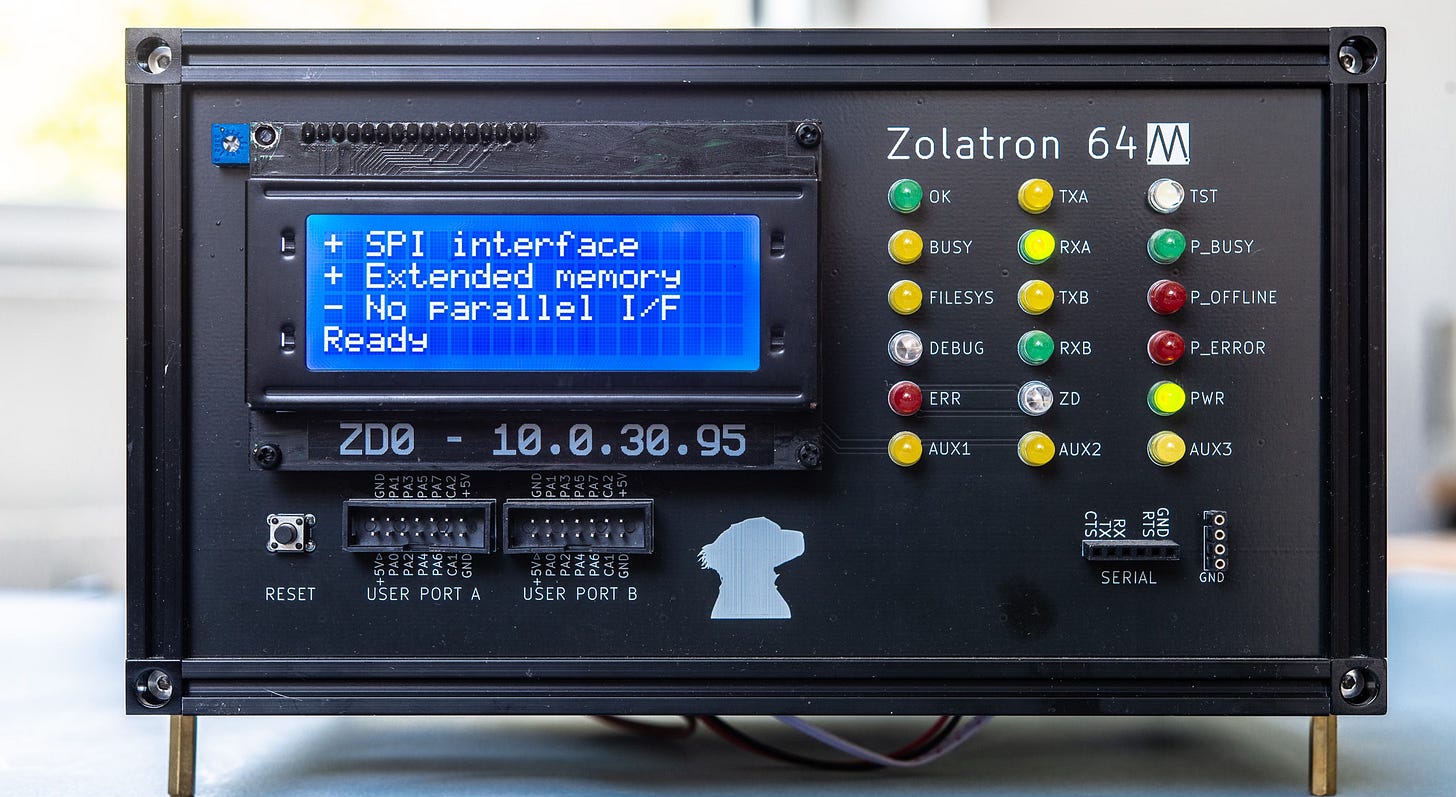

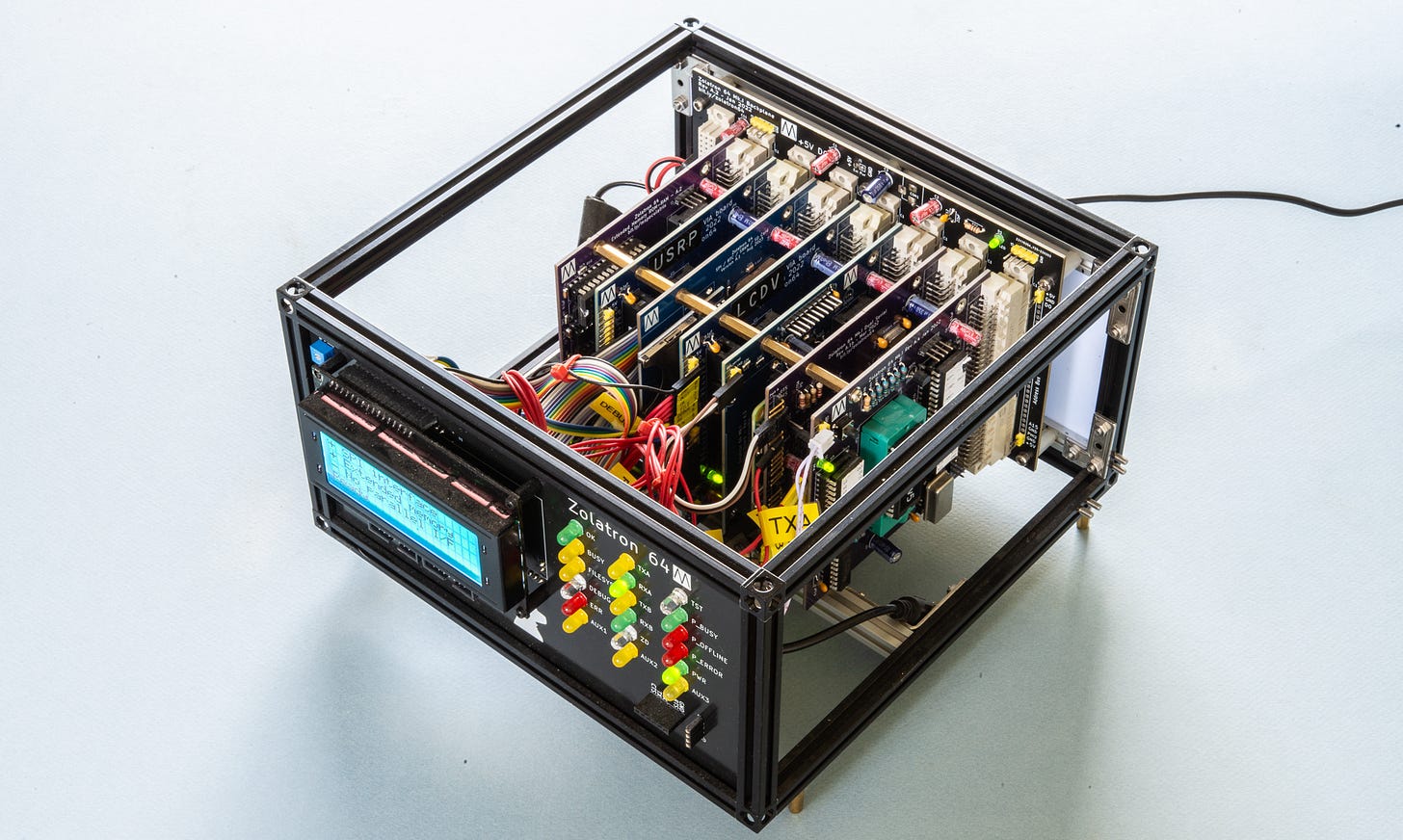

The Zolatron is now built and (mostly) working. But the forthcoming series of articles isn’t going to be merely a retelling of a completed journey. Based on posts from a now-discarded blog and my notebooks, I will be reliving my decisions, mistakes and triumphs. This is a project I haven’t visited in a while and which I need to rediscover, learning the lessons again. And I plan to push it further, adding capabilities and features.

To be clear, this is by no means the cleverest, most elegant or most performant 8-bit homebrew computer you can find. It’s basic, doubtless incorporates many dubious choices and runs at a measly 1MHz. But it’s mine.

I’m not going to tell you how to build a computer. I’m going to tell you how I did it. Maybe my triumphs and mistakes will inspire you to start a project of your own.

There is a GitHub Zolatron repo with the code, datasheets and other documents related to this project.

Steve Mansfield-Devine is a freelance writer, tech journalist and photographer. You can find photography portfolio at Zolachrome, buy his books and e-books, or follow him on Bluesky or Mastodon.

Or you can buy Steve a coffee — it helps keep these projects going.